Introduction

The Ben Franklin Effect is a fascinating psychological phenomenon named after one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, Benjamin Franklin. This principle suggests that if a person does a favor for someone else, they are more likely to do another favor for that person in the future, even if they initially disliked them. In other words, we tend to like people more after we do something kind for them.

This counter-intuitive concept is rooted in cognitive dissonance theory, which states that we strive for consistency in our beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. When there’s a discrepancy (for instance, when we help someone we don’t particularly like), we experience discomfort. To resolve this, we adjust our attitudes and start to like the person we helped.

The Ben Franklin Effect has significant implications in various areas, including social psychology, relationships, business, and persuasion. It’s a powerful tool that can be used to foster positive interactions and build stronger relationships.

We have created a detailed post on 125 most common biases and fallacies. Read Here

History of the Ben Franklin Effect

The Ben Franklin Effect is named after Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, who first observed this phenomenon in action. The story goes that Franklin, in his early political career, encountered a rival legislator who disliked him and opposed his initiatives. Instead of confronting this rival directly, Franklin employed a more subtle strategy.

He asked the rival legislator if he could borrow a rare book from his library. The legislator, flattered by Franklin’s request, lent him the book. After reading it, Franklin returned the book with a note expressing his sincere gratitude. Following this exchange, the rival’s attitude towards Franklin changed significantly. He started speaking to Franklin in friendly terms and ceased his opposition to Franklin’s proposals. This incident led Franklin to conclude that when a person does a favor for someone else, it increases their liking for that person.

This anecdote was later studied by researchers in the field of psychology, who confirmed Franklin’s observations. In the 1960s, the psychologist Jecker and Landy conducted an experiment that validated the Ben Franklin Effect. They found that individuals who were asked to return a favor (in this case, returning money) reported liking the person who asked for the favor more than those who were not asked to return the favor.

Since then, the Ben Franklin Effect has been a subject of interest in social psychology, with numerous studies exploring its implications in various contexts, such as interpersonal relationships, business, and persuasion tactics.

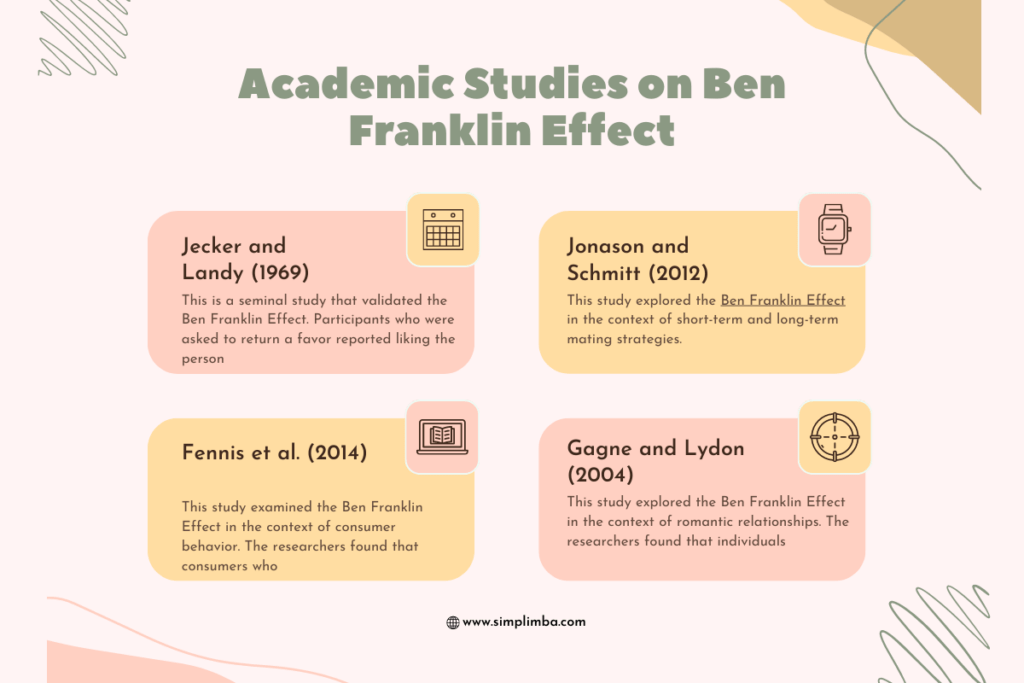

Academic Studies on Ben Franklin Effect

Jecker and Landy (1969): This is a seminal study that validated the Ben Franklin Effect. Participants who were asked to return a favor reported liking the person who asked for the favor more than those who were not asked to return the favor.

Jonason and Schmitt (2012): This study explored the Ben Franklin Effect in the context of short-term and long-term mating strategies. The researchers found that individuals who were more interested in short-term mating were more likely to use the Ben Franklin Effect to their advantage.

Fennis et al. (2014): This study examined the Ben Franklin Effect in the context of consumer behavior. The researchers found that consumers who were asked to do a small favor by a salesperson (such as answering a few questions) were more likely to comply with a larger request later (such as making a purchase).

Gagne and Lydon (2004): This study explored the Ben Franklin Effect in the context of romantic relationships. The researchers found that individuals who did favors for their partners were more likely to feel committed to their relationship.

We have created a detailed post on 125 most common biases and fallacies. Read Here

Examples of Ben Franklin Effect

Example 1: Personal Relationships

Imagine you have a co-worker who you don’t particularly like. One day, they ask you to help them with a project they’re struggling with. You decide to help, and after doing so, you find that your feelings towards this co-worker have become more positive. This is the Ben Franklin Effect in action.

Example 2: Business and Sales

A salesperson at a store asks you to fill out a short survey about your shopping preferences. After you’ve done this small favor, they ask if you’d be interested in one of their products. You find yourself more inclined to consider their offer, again demonstrating the Ben Franklin Effect.

Example 3: Politics

A politician asks for your support in a small way, such as signing a petition or attending a rally. After doing so, you find yourself more supportive of this politician and their platform, even if you were initially indifferent or slightly negative towards them.

Case Study 1: Franklin’s Anecdote

Benjamin Franklin’s Anecdote The most famous real-life case study is the one from which the effect gets its name. Benjamin Franklin, needing to win over a rival legislator, asked to borrow a rare book from the man’s library. After the legislator complied, his attitude towards Franklin softened, and he became more supportive of Franklin’s initiatives.

Case Study 2: Jecker and Landy’s Experiment

Jecker and Landy’s Experiment (1969) In this experiment, participants who won money from the researcher were later asked to return it because the researcher was low on funds. Those who were asked to return the money ended up liking the researcher more than those who were allowed to keep the money. This study provided empirical support for the Ben Franklin Effect.

We have created a detailed post on 125 most common biases and fallacies. Read Here

Ben Franklin Effect in Real-Life Examples

Benjamin Franklin Effect Psychology

The Benjamin Franklin Effect is a psychological principle that suggests if a person does a favor for someone else, they are more likely to develop positive feelings towards that person. This is based on the theory of cognitive dissonance, which states that we strive for consistency in our beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. When there’s a discrepancy, such as when we help someone we don’t particularly like, we experience discomfort. To resolve this, we adjust our attitudes and start to like the person we helped.

Ben Franklin Effect in Relationships

In the context of relationships, the Ben Franklin Effect can be a powerful tool for improving interpersonal dynamics. For instance, if there’s tension between two friends, one might ask the other for a small favor. Once the favor is done, the person who did the favor may find their feelings towards the other person have improved. This can also apply to romantic relationships, where doing favors for each other can strengthen the bond and increase feelings of affection.

Ben Franklin Effect in Social Psychology

Social psychology studies how individuals’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others. The Ben Franklin Effect is a key concept in this field, as it demonstrates how our actions towards others can influence our attitudes and feelings about them. This effect can be seen in various social contexts, such as group dynamics, persuasion tactics, and social influence strategies. It’s a testament to the power of actions in shaping our perceptions and relationships with others.

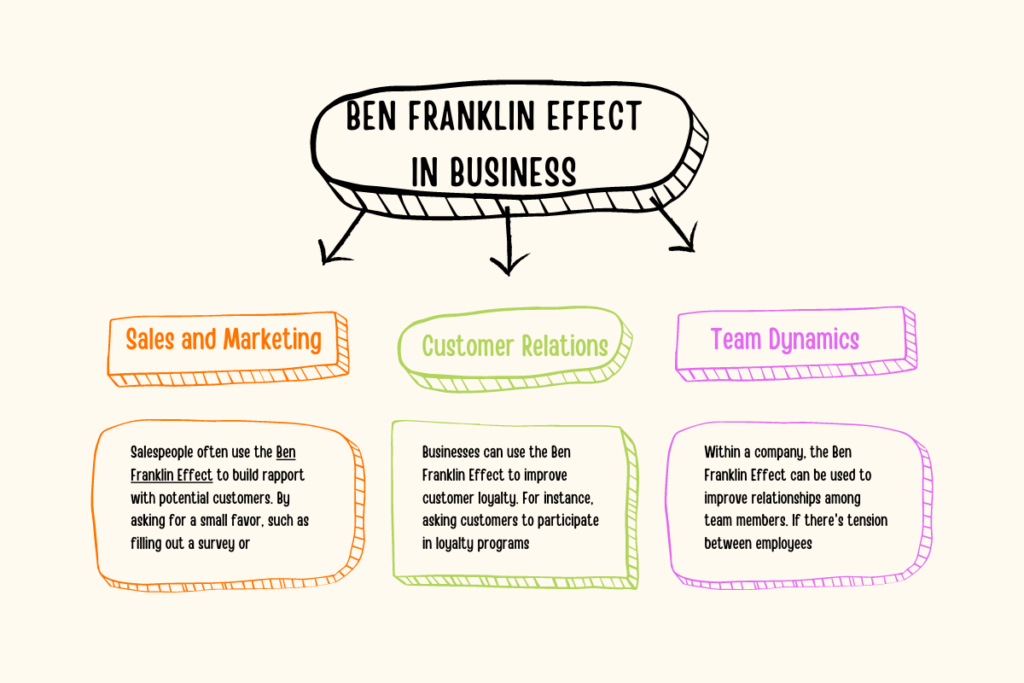

Ben Franklin Effect in Business

Sales and Marketing: Salespeople often use the Ben Franklin Effect to build rapport with potential customers. By asking for a small favor, such as filling out a survey or providing feedback, they can increase the likelihood of the customer complying with a larger request later, such as making a purchase. This strategy can be particularly effective in building long-term customer relationships.

Customer Relations: Businesses can use the Ben Franklin Effect to improve customer loyalty. For instance, asking customers to participate in loyalty programs or provide testimonials can make them feel more invested in the business, leading to increased customer retention.

Team Dynamics: Within a company, the Ben Franklin Effect can be used to improve relationships among team members. If there’s tension between employees, having them do favors for each other can help to reduce conflict and improve cooperation. This can lead to a more positive work environment and increased productivity.

We have created a detailed post on 125 most common biases and fallacies. Read Here

Cognitive Dissonance and Ben Franklin Effect

The Ben Franklin Effect is closely tied to the concept of cognitive dissonance, a theory in psychology that was proposed by Leon Festinger in the 1950s. Cognitive dissonance refers to the mental discomfort or tension that a person experiences when they hold two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or attitudes, or when their behavior contradicts their beliefs or values.

In the context of the Ben Franklin Effect, cognitive dissonance occurs when a person does a favor for someone they dislike. The act of helping contradicts their negative feelings towards the person, creating a state of cognitive dissonance. To resolve this discomfort, the person changes their attitudes and starts to like the person they helped. This is because it’s often easier to change our attitudes than our behaviors.

For example, if you lend a book to a colleague you don’t particularly like, you might experience cognitive dissonance because your action (doing a favor) contradicts your attitude (disliking the colleague). To reduce this dissonance, you might adjust your attitude and start to view your colleague in a more positive light.

This connection between cognitive dissonance and the Ben Franklin Effect illustrates how our actions can influence our attitudes and beliefs, a fundamental principle in social psychology.

Ben Franklin Effect and Likability

The Ben Franklin Effect has a significant impact on likability, which refers to the degree to which a person can be liked by others. This psychological phenomenon suggests that when we do a favor for someone, our brain convinces us that we must like that person to justify our actions. This, in turn, increases our likability towards that person.

Here’s how it works:

When we do a favor for someone, especially if we do so without any apparent external reward, our brain tends to resolve the dissonance between our actions (doing a favor) and our feelings (not particularly liking the person) by adjusting the latter. We start to convince ourselves that we must like the person for whom we did the favor, thereby increasing their likability in our perception.

Moreover, the Ben Franklin Effect can also increase our likability in the eyes of the person for whom we did the favor. When we help someone, they are likely to perceive us as kind and generous, traits that are generally associated with likability. This can lead to a positive cycle where both parties develop increased likability towards each other, fostering stronger and more positive relationships.

Samrat is a Delhi-based MBA from the Indian Institute of Management. He is a Strategy, AI, and Marketing Enthusiast and passionately writes about core and emerging topics in Management studies. Reach out to his LinkedIn for a discussion or follow his Quora Page