Introduction

Defining Anchoring Bias

Anchoring Bias is a cognitive bias that influences our decision-making process. It refers to our tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information we encounter (the ‘anchor’) when making decisions. This initial information sets a mental benchmark that can significantly influence subsequent judgments and decisions.

We have published a list of 125 Most Common Biases and Fallacies. Read here

Layman Example of Anchoring Bias

To understand Anchoring Bias in layman’s terms, consider this example: Suppose you’re shopping for a used car. The seller initially asks for $15,000. That price sets an ‘anchor’ in your mind. Even if you negotiate the price down to $13,000, you feel like you’ve gotten a good deal, even though the car may not actually be worth that much. This is Anchoring Bias in action – the initial price influenced your perception of any subsequent price.

Academic Definitions of Anchoring Bias

In academic terms, Anchoring Bias is a concept in behavioral finance and psychology. It refers to the human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered when making decisions. This initial information is the ‘anchor’, and it becomes a reference point for all subsequent deliberations.

In the context of economic choices, Anchoring Bias can lead to sub-optimal financial decisions. For example, investors might hold onto a stock that’s declining in value because they’ve anchored their perception of the stock’s value to the price they initially paid for it.

Understanding Anchoring Bias, along with other cognitive biases, can help us recognize the hidden influences in our decision-making process and make more rational and informed decisions.

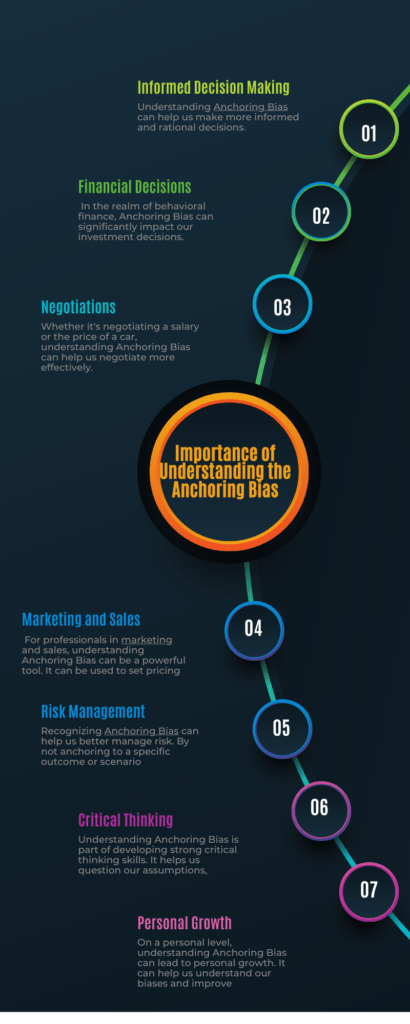

The Importance of Understanding the Anchoring Bias

Informed Decision Making: Understanding Anchoring Bias can help us make more informed and rational decisions. By recognizing when we might be anchoring to a particular piece of information, we can consciously adjust our decision-making process.

Financial Decisions: In the realm of behavioral finance, Anchoring Bias can significantly impact our investment decisions. Recognizing this bias can help us avoid making poor investment choices based on an arbitrary reference point.

Negotiations: Whether it’s negotiating a salary or the price of a car, understanding Anchoring Bias can help us negotiate more effectively. By recognizing the initial offer as an anchor, we can adjust our negotiation strategy accordingly.

Marketing and Sales: For professionals in marketing and sales, understanding Anchoring Bias can be a powerful tool. It can be used to set pricing strategies that take advantage of this bias to influence consumer behavior.

Risk Management: Recognizing Anchoring Bias can help us better manage risk. By not anchoring to a specific outcome or scenario, we can more objectively assess the potential risks and rewards of different options.

Critical Thinking: Understanding Anchoring Bias is part of developing strong critical thinking skills. It helps us question our assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and make more balanced judgments.

Personal Growth: On a personal level, understanding Anchoring Bias can lead to personal growth. It can help us understand our biases and improve our decision-making skills in all areas of life, not just finance or economics

We have published a list of 125 Most Common Biases and Fallacies. Read here

The Psychology behind anchoring Bias

The Anchoring Bias is deeply rooted in our cognitive processes. It’s a psychological heuristic, or mental shortcut, that our brains use to save time when making decisions. Here’s a closer look at the psychology behind it:

Cognitive Load: Our brains are constantly processing a vast amount of information. To manage this cognitive load, our brains often use heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to make quick decisions. Anchoring is one such heuristic. When we anchor, we latch onto the first piece of information we encounter and base our subsequent decisions on this anchor. This process allows us to make decisions more quickly, but it can also lead to biased and irrational decisions.

Perception of Relevance: Often, the information we anchor to is perceived as relevant, even if it’s not. For example, in a negotiation, the initial offer is often seen as a fair estimate of the item’s value, even if it’s just an arbitrary starting point. This perceived relevance of the anchor can strongly influence our subsequent decisions.

Confirmation Bias: Anchoring Bias can also be reinforced by another cognitive bias known as confirmation bias. Once we’ve anchored to a particular piece of information, we tend to seek out and pay more attention to information that supports this anchor, while ignoring information that contradicts it. This can lead to a self-reinforcing cycle of biased decision-making.

Aversion to Loss: In behavioral finance, Anchoring Bias is often linked to loss aversion. For example, investors might anchor to the price they paid for a stock and be reluctant to sell the stock at a lower price, even if the stock’s fundamentals have deteriorated. This is because the potential loss from selling the stock is perceived as greater than the potential gain from holding onto it.

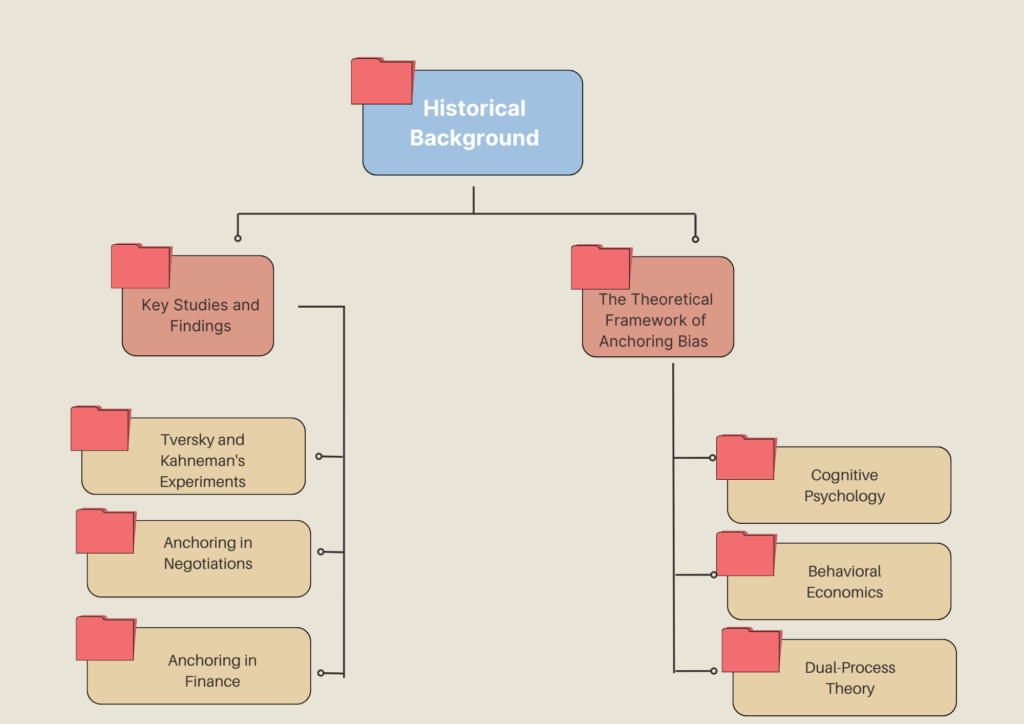

Historical Background

The concept of Anchoring Bias was first introduced by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. As pioneers in the field of behavioral economics, they conducted several experiments to understand how people make decisions under uncertainty.

Their groundbreaking paper, “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,” published in Science in 1974, introduced the concepts of anchoring, availability, and representativeness as heuristics that guide our decision-making process.

Key Studies and Findings

Over the years, numerous studies have been conducted to explore the Anchoring Bias in various contexts. Here are a few key findings:

Tversky and Kahneman’s Experiments: In one of their most famous experiments, Tversky and Kahneman asked participants to estimate the percentage of African nations in the United Nations. Before making their estimate, participants spun a wheel of fortune that landed on a random number. Despite the number being irrelevant, participants’ estimates were influenced by it, demonstrating the power of Anchoring Bias.

Anchoring in Negotiations: In a study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2001, researchers found that in negotiations, the party who makes the first offer often comes out ahead. This is because the first offer sets an anchor that influences the rest of the negotiation.

Anchoring in Finance: In the world of finance, a study published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization in 2013 found that professional stock market forecasters tend to anchor their predictions to recent stock market performance, demonstrating the influence of Anchoring Bias in financial decision-making.

The Theoretical Framework of Anchoring Bias

The theoretical framework of Anchoring Bias is rooted in cognitive psychology and behavioral economics. It’s based on the idea that when making decisions, individuals rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive, known as the ‘anchor’. Subsequent judgments are then made by adjusting away from this anchor.

Cognitive Psychology

From a cognitive psychology perspective, Anchoring Bias is seen as a mental heuristic that individuals use to reduce the complexity of decision-making. When faced with complex decisions, individuals often use heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to simplify the decision-making process. Anchoring is one such heuristic, where individuals use an initial piece of information to reduce uncertainty and facilitate decision-making.

Behavioral Economics

In the field of behavioral economics, Anchoring Bias is viewed as a systematic error that individuals make when forming economic expectations or making economic decisions. It’s considered a cognitive bias that can lead to irrational economic behavior. For example, investors might anchor to the price they paid for a stock and be reluctant to sell the stock at a lower price, even if the stock’s fundamentals have deteriorated.

Dual-Process Theory

The Dual-Process Theory, another theoretical framework often associated with Anchoring Bias, suggests that our thinking process is governed by two systems: System 1, which is fast, intuitive, and often prone to bias, and System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and more logical. Anchoring Bias is often attributed to System 1 thinking, as the act of anchoring to a particular piece of information is usually an automatic and intuitive process.

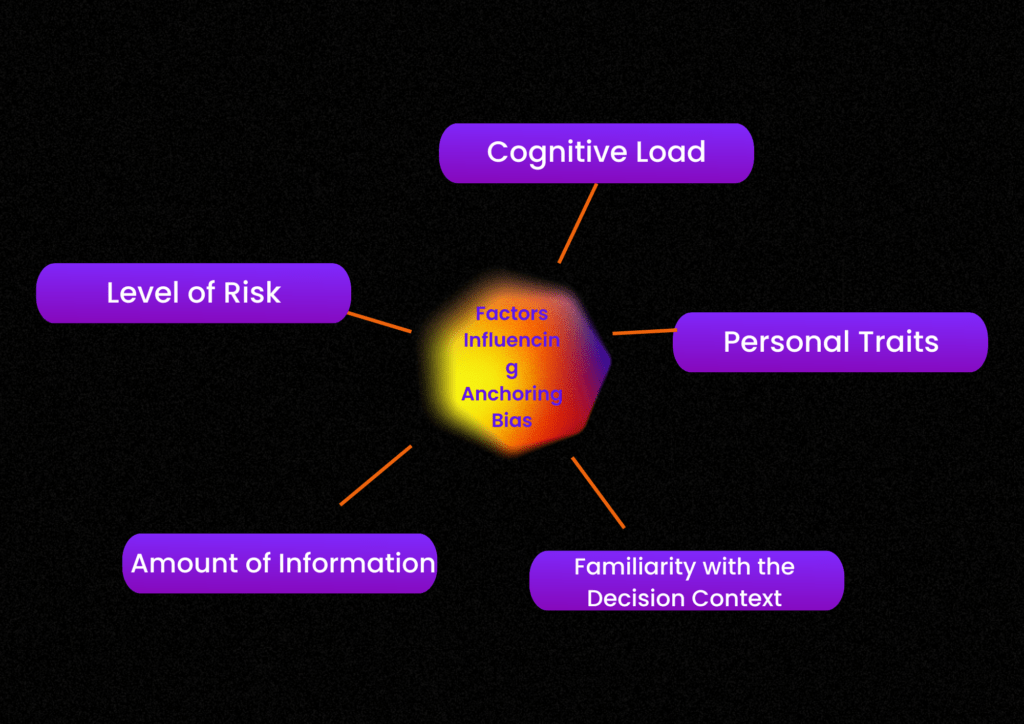

Factors Influencing Anchoring Bias

Level of Risk: The Anchoring Bias often becomes more pronounced in situations where the outcomes are perceived as risky. When faced with uncertainty, individuals tend to prefer known risks over unknown risks, demonstrating an irrational bias towards the initial anchor.

Amount of Information: The less information available, the more likely individuals are to exhibit the Anchoring Bias. When there’s a lack of information about an option, individuals often choose the option with more available information, even if it’s not necessarily the best choice.

Familiarity with the Decision Context: The Anchoring Bias can be influenced by how familiar an individual is with the decision context. For example, market participants who are familiar with the fluctuations in stock prices may feel more comfortable making investment decisions despite the ambiguity.

Personal Traits: Certain personal traits, such as tolerance for ambiguity and risk-taking propensity, can influence the extent to which an individual exhibits the Anchoring Bias. Individuals with a high tolerance for ambiguity and a high propensity for risk-taking may be less influenced by this bias.

Cognitive Load: The Anchoring Bias can be exacerbated when individuals are under a high cognitive load, meaning they’re trying to process too much information at once. When cognitive load is high, individuals may be more likely to rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, leading to the Anchoring Bias.

We have published a list of 125 Most Common Biases and Fallacies. Read here

Real-World Implications of Anchoring Bias

The Anchoring Bias has significant real-world implications, particularly in the fields of behavioral finance, economics, and business. Here’s how this cognitive bias can influence various aspects of our lives:

Financial Decisions: In the realm of behavioral finance, Anchoring Bias can significantly impact our investment decisions. For instance, investors might anchor to the price they paid for a stock and be reluctant to sell the stock at a lower price, even if the stock’s fundamentals have deteriorated. This can lead to sub-optimal financial decisions and potential financial losses.

Economic Choices: Anchoring Bias can also influence broader economic choices. For example, in price negotiations, the seller’s initial price (the anchor) can significantly influence the final agreed-upon price. This demonstrates how Anchoring Bias can have real-world implications on our economic choices and financial wellbeing.

Business and Marketing: In business and marketing, understanding Anchoring Bias can be a powerful tool. It can be used to set pricing strategies that take advantage of this bias to influence consumer behavior. For example, setting a higher initial price for a product can make subsequent discounts seem more attractive, thereby increasing sales.

Research and Data Analysis: In research and data analysis, Anchoring Bias can lead to skewed results. If researchers anchor to a specific hypothesis or expectation, they may unconsciously interpret the data in a way that confirms their initial beliefs. This can lead to biased results and inaccurate conclusions.

Everyday Decision Making: On a personal level, Anchoring Bias can influence our everyday decisions, from how much we’re willing to pay for a product to how we interpret news and information. By being aware of this bias, we can strive to make more rational and unbiased decisions.

Negotiation Strategies: Recognizing the Anchoring Bias can be advantageous in negotiations. By being aware of the anchor’s influence, individuals can strategically set their own anchors to guide the negotiation process and influence the final outcome. This applies to both price negotiations and other forms of negotiation, such as contract terms or project timelines.

Marketing and Advertising: Anchoring Bias plays a crucial role in marketing and advertising. Marketers often use price anchoring techniques to influence consumer perceptions. By displaying a higher initial price or comparing it to a higher reference price, they can create the perception of a better deal, leading to increased sales and customer satisfaction.

Consumer Behavior: The Anchoring Bias affects consumer decision-making and purchasing behavior. Consumers tend to rely on initial information, such as product features or price, as an anchor when evaluating alternatives. This bias can influence their perception of value, willingness to pay, and ultimately their purchase decisions.

Investment Evaluation: Anchoring Bias can impact investment evaluation. When considering financial investments, individuals may anchor their expectations to historical returns or the opinions of others. This bias can cloud judgment and lead to skewed assessments of investment opportunities, potentially resulting in suboptimal investment decisions.

Product Pricing: Anchoring Bias influences product pricing strategies. Companies often introduce higher-priced versions or premium options to anchor consumer perceptions. By offering a higher-priced option alongside lower-priced alternatives, they create a contrast that makes the lower-priced options appear more attractive.

Decision-Making Processes: The Anchoring Bias can influence various decision-making processes, such as hiring, project planning, or resource allocation. Anchors, whether salary expectations, initial project estimates, or budget figures, can heavily influence subsequent judgments, leading to biased outcomes if not carefully considered.

Risk Assessment: Anchoring Bias can impact risk assessment and risk management. When evaluating risks, individuals may anchor to specific scenarios or historical data, potentially overlooking other important risk factors. This bias can hinder accurate risk assessment and result in inadequate risk management strategies.

Personal Finance: Anchoring Bias can affect personal financial decisions, such as budgeting, saving, and spending habits. Individuals may anchor their perception of “normal” spending levels to past experiences or external influences, leading to financial habits that may not align with their actual financial goals.

Entrepreneurship and Innovation: The Anchoring Bias can impact entrepreneurship and innovation by limiting individuals’ willingness to take risks. Entrepreneurs anchored to previous failures or industry norms may avoid pursuing innovative ideas, hindering their ability to create groundbreaking solutions or disrupt existing markets.

Awareness and Recognition: The first step in overcoming Anchoring Bias is to be aware of its presence and actively recognize when it may be influencing your decision-making process. By acknowledging the potential for anchoring, you can consciously work to mitigate its effects.

Broaden Perspectives: Seek out a variety of perspectives and alternative viewpoints to challenge the initial anchor. Engage in discussions with others who may have different opinions or expertise. This can help expand your thinking and reduce the impact of the initial anchor on your decision.

Generate Multiple Options: Encourage the generation of multiple options before settling on a decision. By considering a range of possibilities, you can avoid fixating on a single anchor and explore a broader spectrum of choices.

Delay Judgments: Resist the impulse to make quick judgments based solely on the initial anchor. Take the time to gather additional information and thoroughly evaluate the options available. Delaying judgments allows for a more considered and independent decision-making process.

Use Comparative Analysis: Compare and evaluate alternatives based on their own merits, rather than in relation to the initial anchor. Consider factors such as financial decisions, economic choices, and market participants. Analyze each option independently to prevent the biasing effects of anchoring.

Diverse Reference Points: Seek out a range of reference points beyond the initial anchor. Consider different sources of information, historical data, expert opinions, or anchoring bias examples. By incorporating a diverse set of references, you can create a more comprehensive and balanced perspective.

Implement Decision-Making Tools: Utilize decision-making tools such as decision matrices, cost-benefit analyses, or anchoring and adjustment techniques. These tools can help structure your decision-making process, facilitating a more systematic evaluation of options and reducing the influence of anchoring.

Encourage Independent Analysis: Encourage independent analysis and critical thinking. Encourage others involved in the decision-making process to challenge the initial anchor and provide their own assessments. This fosters a more objective evaluation of options and reduces the impact of anchoring bias.

Reflect and Learn: After making a decision, reflect on the process and outcome. Assess whether the initial anchor unduly influenced your judgment and consider how you can improve your decision-making skills in future scenarios. Learning from past experiences helps to refine your ability to overcome anchoring bias.

Samrat is a Delhi-based MBA from the Indian Institute of Management. He is a Strategy, AI, and Marketing Enthusiast and passionately writes about core and emerging topics in Management studies. Reach out to his LinkedIn for a discussion or follow his Quora Page