In a world increasingly driven by information exchange, the role of mass communication in shaping our perceptions, behaviors, and decisions cannot be overstated. Welcome to our deep dive into the riveting realm of mass communication theories. A space where we dissect, discuss, and demystify the complex mechanisms that dictate how information is shared and processed on a large scale. Whether you’re a seasoned communication professional, a budding scholar, or simply a curious mind, this exploration promises to be both enlightening and engaging.

Understanding the theories of mass communication is more than just an academic exercise. It’s a key to unlocking the potential of strategic communication in our personal and professional lives. It’s about gaining insights into how messages are crafted, disseminated, and interpreted, and how these processes impact our society. With a blend of compelling data, authoritative insights, and a dash of wit, we’ll journey through these theories, uncovering their relevance in today’s hyper-connected world. So, get ready to be captivated, challenged, and ultimately, empowered with a new understanding of the power of communication.

25 Mass Communication Theories

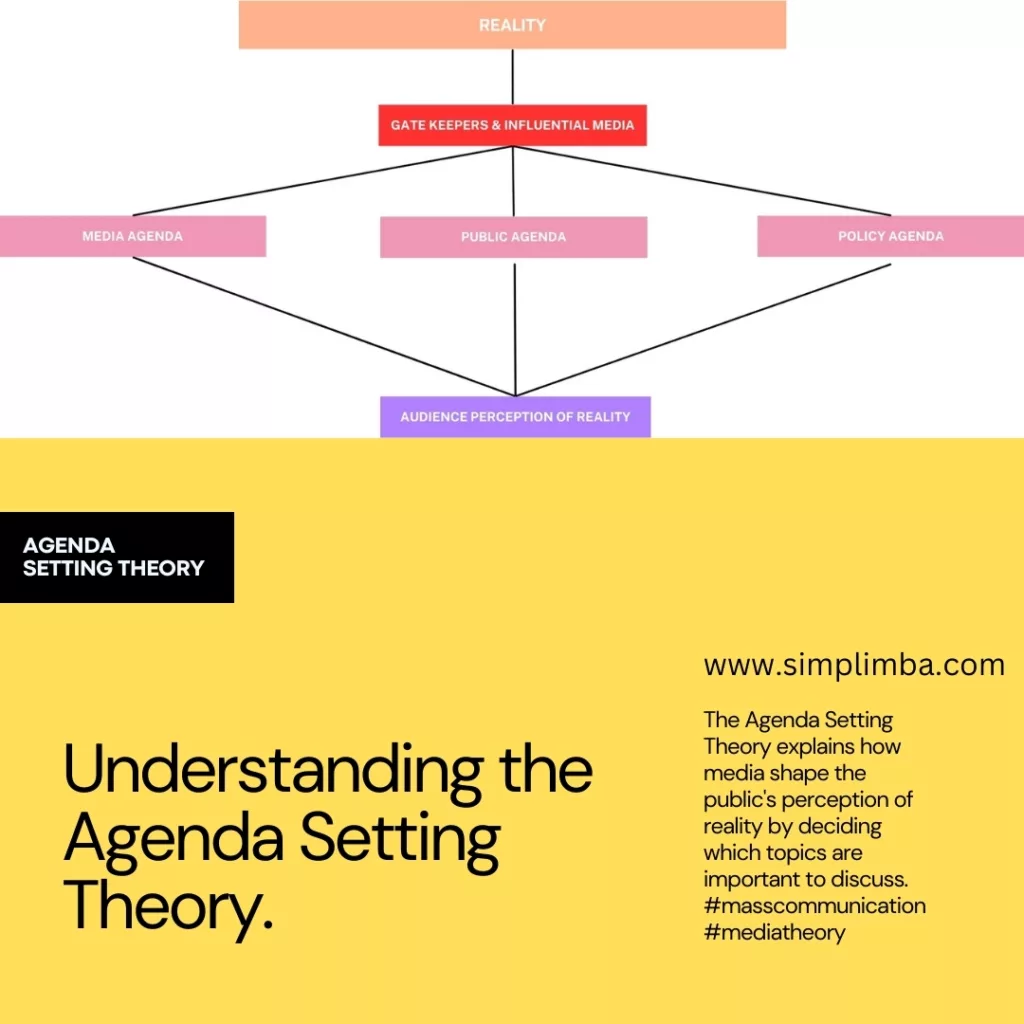

Agenda-Setting Theory

This theory posits that media has the power to determine which issues are important to the public. The Agenda-Setting Theory, coined by Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw in the late 1960s, is a concept in mass communication that asserts the media’s power in shaping public perception of what issues are important. It suggests that the media doesn’t necessarily tell us what to think, but rather what to think about.

The crux of this theory lies in the media’s ability to influence the salience of topics within the public sphere. For instance, if news outlets consistently cover climate change, the public will perceive it as a critical issue needing attention. Conversely, issues that receive little to no media coverage may be perceived as unimportant, regardless of their actual significance.

An example of this can be seen in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Media outlets heavily focused on the personalities of the candidates rather than their policy positions. As a result, the public discourse was centered around the candidates’ character traits rather than the policies they proposed.

The Agenda-Setting Theory was born out of a study McCombs and Shaw conducted during the 1968 U.S. Presidential Election. They found a strong correlation between what the media highlighted as important issues and what voters perceived as important issues. This led to the conclusion that the media was setting the agenda for public discussion.

In today’s digital age, the Agenda-Setting Theory remains highly relevant. With the advent of social media, the power to set the agenda has become even more potent. News outlets, influencers, and even ordinary individuals can shape public perception of what issues are important, thus steering the direction of public discourse.

Cultivation Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Cultivation Theory

The Cultivation Theory, developed by George Gerbner in the mid-1960s, is a social theory which examines the long-term effects of television on its viewers’ perceptions of reality. Gerbner, a professor of communication, proposed that the more time people spend ‘living’ in the television world, the more likely they are to believe social reality aligns with the reality portrayed on television.

At the crux of the Cultivation Theory is the concept of the “mean world syndrome”. This suggests that individuals who watch a lot of television are likely to perceive the world as more dangerous and violent than it is. For instance, if someone watches a lot of crime shows, they may develop an exaggerated fear of becoming a victim of crime, even if they live in a relatively safe area. This is because their perception of reality has been ‘cultivated’ by the images and ideas presented on television.

The theory was initially formulated during a time when television was the primary medium for entertainment and information. However, its implications extend to our current era, where mass media consumption has diversified across various platforms like social media, streaming services, and online news outlets.

In the context of modern mass communication, the Cultivation Theory remains highly relevant. Today, it’s not just television but also digital media that has a profound impact on how we perceive and understand the world around us. For instance, constant exposure to picture-perfect lives on Instagram can cultivate a belief that everyone else’s life is happier and more successful, causing feelings of inadequacy or dissatisfaction. Similarly, continuous exposure to violent news stories can create a perception that the world is more dangerous than it is.

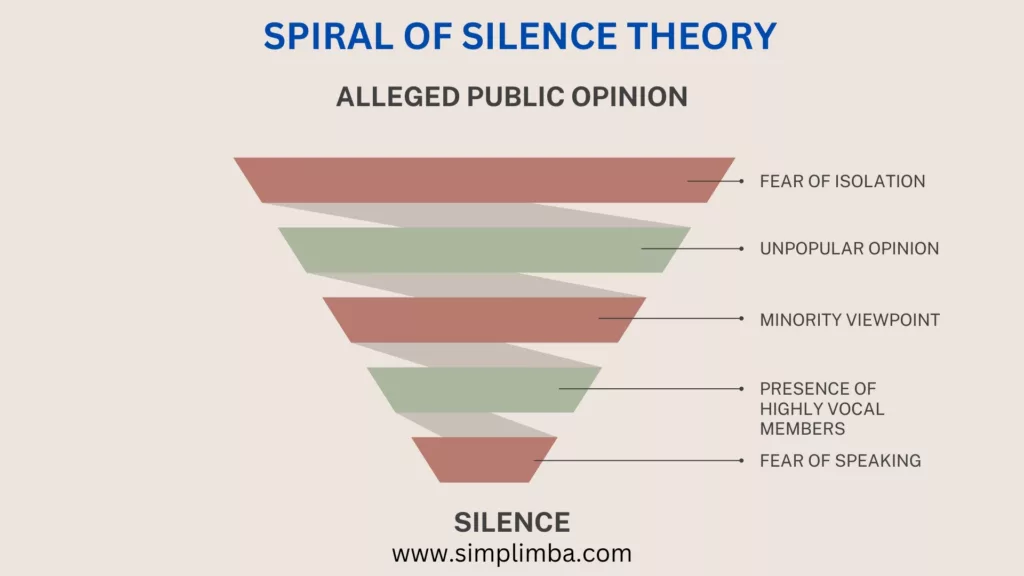

Spiral of Silence Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Spiral of Silence Theory

The Spiral of Silence Theory, first introduced by German political scientist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann in 1974, is a sociological and psychological theory that explains why people are reluctant to express their opinions when they believe they are in the minority. The theory suggests that this self-censorship stems from the fear of isolation, a fundamental human instinct. Individuals, fearing social isolation or reprisal, tend to remain silent rather than voice unpopular views. This creates a spiraling effect, where the perceived majority opinion becomes even more dominant as minority voices quiet down.

For example, consider a workplace scenario where the majority of employees agree with a new policy introduced by management. An employee who disagrees might choose to remain silent rather than voice their dissent, fearing ostracization or negative repercussions. This silence further reinforces the perceived popularity of the policy, creating a ‘spiral’ of silence.

The Spiral of Silence Theory has its roots in the study of public opinion, particularly in the context of mass media and its role in shaping societal norms and perceptions. Noelle-Neumann’s theory was a response to the observation that public opinion seemed to have a powerful influence over individual behaviors and attitudes, even when it didn’t align with personal beliefs.

In the modern context, the Spiral of Silence Theory has significant relevance in the realm of mass communication, particularly in the age of social media. It helps explain phenomena like ‘echo chambers’ or ‘filter bubbles’, where individuals are more likely to be exposed to similar viewpoints and less likely to encounter dissenting opinions. This can lead to a skewed perception of public opinion, further exacerbating the spiral of silence.

Understanding this theory is crucial for communicators, marketers, and influencers who aim to encourage open dialogue, foster diversity of opinion, and challenge dominant narratives. It also highlights the importance of creating safe spaces for minority voices and dissenting opinions to be heard and respected.

Uses and Gratifications Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Uses and Gratification Theory

The Uses and Gratifications Theory, a popular approach in media studies, posits that individuals actively seek out specific media sources to satisfy particular needs or desires. This theory challenges the traditional notion of passive media consumption, arguing instead that consumers play an active role in choosing and interpreting the media they consume based on their personal and psychological needs.

For instance, a person might choose to watch a comedy show to fulfill their need for relaxation and entertainment, or read a newspaper to satisfy their need for knowledge and staying updated. In the realm of digital media, one might use social media platforms like Facebook to satisfy their need for social interaction and community.

The Uses and Gratifications Theory evolved in the 1970s, during a time when researchers began to shift their focus from what media does to people, to what people do with media. This shift was driven by the growing dissatisfaction with the limited effects perspective, which posited that media had a direct and powerful influence on audiences. Scholars like Elihu Katz, Jay G. Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch were instrumental in the development of this theory, emphasizing the active role of the audience in their media consumption.

In the era of digital media, the Uses and Gratifications Theory is more relevant than ever. Today’s consumers have an unprecedented level of control over their media consumption, with the ability to choose what they want to consume, when they want to consume it, and on what platform.

Moreover, the rise of social media has added a new dimension to this theory. Social media platforms not only satisfy traditional needs like information and entertainment but also fulfill social and interactive needs. For instance, users might use Instagram to express their creativity, LinkedIn for professional networking, or Twitter for real-time news and discussions.

Media Dependency Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Media Dependence Theory

Suggests that the more dependent an individual is on the media for having his or her needs fulfilled, the more important the role the media plays in the person’s life

The Media Dependency Theory, conceptualized by Sandra Ball-Rokeach and Melvin DeFleur in 1976, proposes that the more an individual relies on media to meet their needs, the more significant the role media will play in their life. This theory is grounded in the idea that people use media to understand their world and create social realities. The degree of a person’s dependency on media varies based on the number and quality of their direct real-life information sources and experiences.

For instance, a person living in a remote area with limited social interaction may rely heavily on television or social media to understand the wider world. Here, the media plays a pivotal role in shaping their perceptions and beliefs. On the other hand, someone living in a bustling city with diverse social interactions may have a lesser dependency on media as they have more direct sources of information and experiences.

The Media Dependency Theory emerged during the mid-1970s, a period marked by significant societal changes. The Vietnam War, Watergate scandal, and civil rights movements were dominating the media landscape, and people were increasingly turning to media sources for information and understanding. Recognizing this shift, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur developed the theory to explain the growing power and influence of media on individuals and societal perceptions.

In today’s digital age, the Media Dependency Theory is more relevant than ever. With the advent of the internet and social media, people’s reliance on media for information, entertainment, and social interaction has increased exponentially. Media platforms have become primary sources for news, shaping public opinion and even influencing political outcomes.

For instance, consider the role of social media in recent political campaigns. Candidates use platforms like Twitter and Facebook to communicate directly with voters, bypassing traditional media outlets. Voters, in turn, rely on these platforms for information about the candidates, making them more susceptible to the messages conveyed through these channels.

Social Learning Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Social Learning Theory

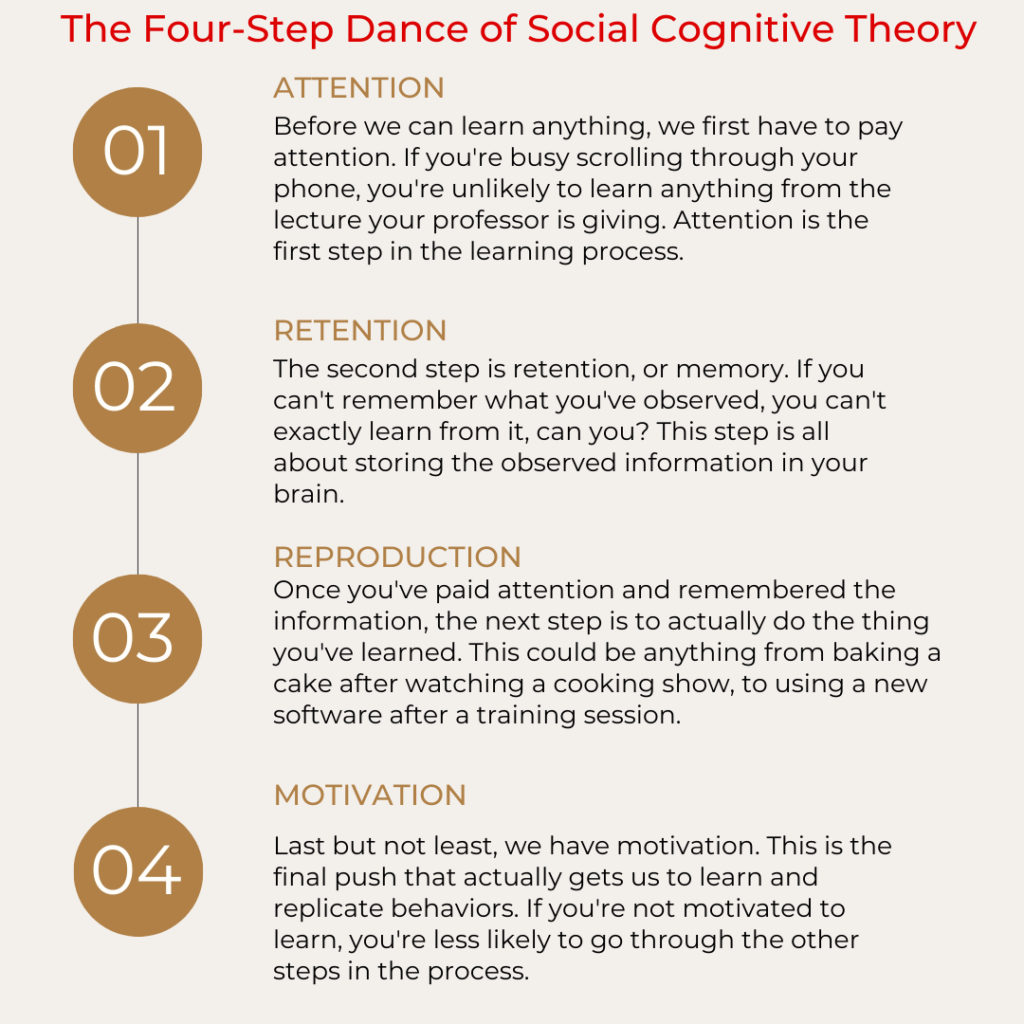

The Social Learning Theory, primarily developed by psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1960s, posits that individuals learn and acquire new behaviors by observing others. This theory was a groundbreaking shift from traditional learning theories which emphasized learning solely from direct experience. Bandura proposed that we could also learn by watching others and modeling their behavior, hence the term ‘observational learning’.

At the heart of the Social Learning Theory is the concept that individuals observe the behavior of others, and the consequences of those behaviors, and subsequently decide whether to replicate the behavior based on its perceived rewards or punishments. This process is often referred to as vicarious reinforcement.

For instance, consider a child who observes their older sibling being rewarded for completing household chores. The child, seeing the positive outcome (reward), may be motivated to replicate the behavior (doing chores) in hopes of receiving a similar reward.

The Social Learning Theory also introduced the idea of self-efficacy, which is the belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task. Bandura argued that self-efficacy plays a crucial role in determining what we learn and how we behave.

In the context of modern mass communication, the Social Learning Theory holds significant relevance. The rise of social media and digital platforms has amplified the opportunities for observational learning. For example, individuals may observe the behaviors and lifestyles of influencers, celebrities, or peers on social media and may be motivated to emulate these behaviors, whether it’s adopting a certain fashion style, buying a recommended product, or even adopting a particular viewpoint or attitude.

Moreover, marketers and advertisers often leverage the principles of Social Learning Theory to influence consumer behavior. By showcasing the positive outcomes of using a product or service through testimonials, reviews, or influencer endorsements, they tap into the audience’s propensity for observational learning, encouraging them to purchase and use the product.

Gatekeeping Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Gate Keeper Theory

The Gatekeeping Theory, first introduced by social psychologist Kurt Lewin in 1943, is a critical concept in mass communication and journalism. It underscores the power that journalists, editors, news directors, and other media professionals have in controlling the flow of news.

At its core, the Gatekeeping Theory prescribes that these “gatekeepers” decide what information becomes news and what does not. They are the ones who filter the vast amount of information, selecting the stories that are deemed important or relevant and discarding the rest. This process is influenced by various factors, including the gatekeeper’s personal beliefs, organizational policies, societal values, and the perceived interests of the audience.

For instance, consider a news editor working in a national newsroom. They are inundated with numerous stories every day – from political developments and economic news to celebrity gossip and local events. It’s their job to decide which of these stories will make it to the front page or the prime-time news slot. They might prioritize a significant political event over a celebrity scandal, deeming it more newsworthy and relevant to their audience.

The Gatekeeping Theory emerged during World War II, a period when information control was crucial. Lewin’s research was initially focused on the food choices and shopping habits of housewives, but his findings were soon applied to mass communication, revolutionizing the way we understand news dissemination.

In today’s digital age, the relevance of the Gatekeeping Theory has evolved. With the proliferation of social media platforms and the democratization of information, the traditional gates are being bypassed, and the power to control information is shifting to the audience. However, gatekeeping still exists, albeit in a different form. Algorithms on social media platforms now act as the new gatekeepers, filtering and personalizing the content we see based on our online behavior.

Despite these changes, the Gatekeeping Theory remains a vital tool in understanding the dynamics of news production and dissemination. It highlights the power dynamics in media organizations and the role of journalists in shaping public discourse. It also raises important questions about objectivity, bias, and the responsibility of media in a democratic society.

Two-Step Flow Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Two-Step Theory

The crux of the Two-Step Flow Theory lies in its proposition that information dissemination from the media to the general public is not a direct, one-way flow. Instead, it occurs in two distinct stages. First, opinion leaders – individuals who are active media users and who interpret media messages in their own way – absorb the information. These opinion leaders then pass on their interpretations to a wider population, thus indirectly shaping public opinion.

For instance, consider the launch of a new smartphone. The media broadcasts information about its features, price, and availability. Opinion leaders, such as tech bloggers or influencers, pick up this information, analyze it, and share their opinions with their followers. These followers, in turn, are influenced by the opinion leaders’ interpretations and make their purchase decisions accordingly.

The Two-Step Flow Theory was first introduced by sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet in the 1940s, based on their research during the 1940 Presidential election in the U.S. They found that people were more likely to be influenced by interpersonal relationships than direct media messages, challenging the then-dominant “Hypodermic Needle Theory” or “Magic Bullet Theory” which suggested that mass media had a direct, powerful, and immediate effect on audiences.

In the context of modern mass communication, the Two-Step Flow Theory is highly relevant, especially with the rise of social media platforms. Today, influencers, bloggers, and other opinion leaders play a pivotal role in shaping public opinion on everything from consumer products to political ideologies. Brands and organizations often leverage these opinion leaders to effectively communicate their messages to the target audience.

Hypodermic Needle Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Hypodermic Needle Theory

Suggests that media messages are injected directly into the brains of a passive audience Hypodermic Needle Theory, also known as the Magic Bullet Theory, is a model of communication suggesting that an intended message is directly received and wholly accepted by the receiver. The theory was developed in the 1920s and 1930s after researchers observed the effects of propaganda during World War I and the influence of advertising in the 1930s.

The crux of the Hypodermic Needle Theory is that mass media has a direct, immediate, and powerful effect on its audiences. The media ‘shoots’ or ‘injects’ its messages straight into the ‘vein’ of the audience, who passively receive the message without any opportunity for negotiation or interpretation. The audience is seen as a ‘sitting duck’ waiting to be injected with appropriate information.

For instance, consider an advertising campaign for a new smartphone. According to the Hypodermic Needle Theory, if the advertisement is compelling enough, viewers will immediately be influenced to buy the smartphone. The theory assumes that the audience is a homogeneous group that is uniformly susceptible to the messages.

However, this theory has been largely criticized for its simplistic view of communication. It underestimates the power of individual interpretation and the influence of cultural and social contexts. The audience is not merely passive but actively interprets and makes sense of the messages based on their individual experiences and beliefs.

Despite its criticisms, the Hypodermic Needle Theory is still relevant in today’s mass communication landscape. It underscores the potential power of the media in shaping public opinion. However, the rise of digital and social media has made the communication process more interactive and complex, challenging the one-way, direct influence model of the Hypodermic Needle Theory.

Selective Exposure Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Selective Exposure Theory

The Selective Exposure Theory is a concept in psychology that suggests individuals prefer to access information that aligns with their beliefs and values, while actively avoiding information that contradicts them. This theory is rooted in the idea that humans are naturally inclined to seek consistency in their beliefs and attitudes.

The theory was first proposed by psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s as part of his broader theory of cognitive dissonance. Festinger suggested that we experience discomfort when we hold two conflicting beliefs or when our behavior doesn’t align with our beliefs. To reduce this discomfort, we either change our beliefs or behavior, or we avoid information that highlights the inconsistency.

An everyday example of this theory in action can be seen in the realm of politics. People tend to consume news from sources that align with their political beliefs. A conservative might choose to watch Fox News and avoid CNN, while a liberal might do the opposite. They selectively expose themselves to viewpoints that confirm their existing beliefs, while avoiding those that challenge them.

In the age of digital media and mass communication, the Selective Exposure Theory has gained even more relevance. With the advent of social media and personalized news feeds, people have more control over the information they consume. This leads to the creation of “echo chambers” or “filter bubbles” where one’s beliefs are continuously reinforced while opposing views are filtered out.

This theory is of particular interest to marketers and advertisers as it can help them understand their audience’s behavior and tailor their messages accordingly. Knowing that consumers are more likely to engage with information that aligns with their beliefs, marketers can craft messages that resonate with their target audience’s values and needs.

However, the Selective Exposure Theory also raises ethical concerns. It can lead to a polarized society where people only hear one side of the story, leading to a lack of understanding and empathy for different viewpoints. Therefore, media outlets and individuals must strive for balanced information consumption and critical thinking. 11.

Framing Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Framing Theory

The crux of the Framing Theory lies in its definition: it is a communication theory that suggests media not only reports on events but also shapes the way audiences understand and interpret the meaning of these events. In essence, the media ‘frames’ our understanding of the world around us.

For instance, consider a news story about climate change. If the media frames this issue as an imminent disaster, the audience will likely perceive it as a serious problem requiring immediate action. Conversely, if the media frames climate change as a contentious debate, the audience might view it as a less pressing issue.

The Framing Theory has its roots in the field of sociology, but it became more prominent in mass communication research in the 1970s. Scholars such as Erving Goffman and Robert Entman pioneered the study of media framing. Goffman, in his 1974 book “Frame Analysis,” suggested that people interpret what they see and hear based on their previous experiences and societal norms.

Fast forward to the present day, the Framing Theory remains highly relevant in mass communication. In an era of information overload, media outlets often use framing to simplify complex issues and guide the audience toward a particular interpretation. This can be seen in the way political issues are framed during election campaigns, or how public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic are reported.

However, the power of framing also comes with ethical responsibilities. Media professionals must be aware of their influence and strive to present balanced and fair frames that respect the diversity of audience perspectives. As consumers of media, we also need to be critical of the frames presented to us and seek out multiple perspectives to form our understanding.

Priming Theory

Mass Communication Theories: Priming Theory in Mass Communication

The Priming Theory is a psychological concept that suggests exposure to one stimulus influences the response to a subsequent stimulus, without any conscious guidance or intention. The term “priming” refers to the process by which exposure to certain information or experiences can influence an individual’s thoughts, feelings, or behaviors later on, even if they are not aware of the connection. This theory has its roots in cognitive psychology and it has been extensively studied since the 1970s.

In the context of media and communication, the Priming Theory suggests that media images, messages, or experiences can stimulate related thoughts in the minds of audience members. For example, a commercial for a fast-food restaurant might not only make viewers think about the specific brand advertised, but also stimulate thoughts about hunger, convenience, or the pleasure of eating. These related thoughts can then influence the viewer’s subsequent behavior, such as their decision to buy fast food.

In the history of this theory, it was initially studied in relation to memory recall. Researchers found that exposure to a certain stimulus could “prime” an individual’s memory, making related information more accessible. Over time, this concept has been applied to various fields, including marketing and mass communication. Marketers use priming to influence consumer behavior by subtly suggesting certain ideas or associations.

In modern-day mass communication, the Priming Theory remains highly relevant. With the rise of digital media, audiences are constantly being exposed to a myriad of stimuli. Advertisers and content creators can use priming to guide audience behavior in subtle ways. For instance, a news article about climate change might prime readers to think more about environmental issues, influencing their subsequent actions such as supporting green initiatives or reducing their carbon footprint.

Symbolic Interactionism

Mass Communication Theories: Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic Interactionism is a sociological theory that emphasizes the role of symbols and language as core elements of all human interactions. Developed by American sociologist George Herbert Mead in the early 20th century, this theory posits that people act towards things based on the meaning those things have for them, and these meanings are derived from social interaction and modified through interpretation.

In the context of Symbolic Interactionism, the ‘self’ is not a static entity but a dynamic one, constantly being shaped and reshaped through interactions with others and the larger social world. For example, a teenager may see himself as a ‘rebel’ due to the reactions and feedback he gets from his peers and society for his actions and behaviors. The ‘rebel’ label becomes a symbol that influences his self-concept and guides his future actions.

This theory has a rich history, with roots in the work of early sociologists and philosophers like Max Weber and Charles Horton Cooley. However, it was George Herbert Mead who is largely credited with its development. Mead believed that the mind and self were directly shaped by social interaction, not biological factors, a radical thought at the time.

In the modern context, Symbolic Interactionism has profound implications for mass communication. It helps us understand how media messages are interpreted by individuals within their unique social contexts. For instance, a political advertisement might use the symbol of a ‘lion’ to represent strength and leadership. However, the way this symbol is interpreted can vary greatly among individuals, depending on their personal experiences and social backgrounds.

Moreover, with the advent of social media, Symbolic Interactionism takes on even greater relevance. The ‘self’ is continually being presented and re-presented online, shaped by the ‘likes’, comments, and shares we receive. The symbols we use to represent ourselves in these virtual spaces – from the profile pictures we choose, to the emojis we use – all play a part in the ongoing construction of our digital ‘self’.

Media Richness Theory

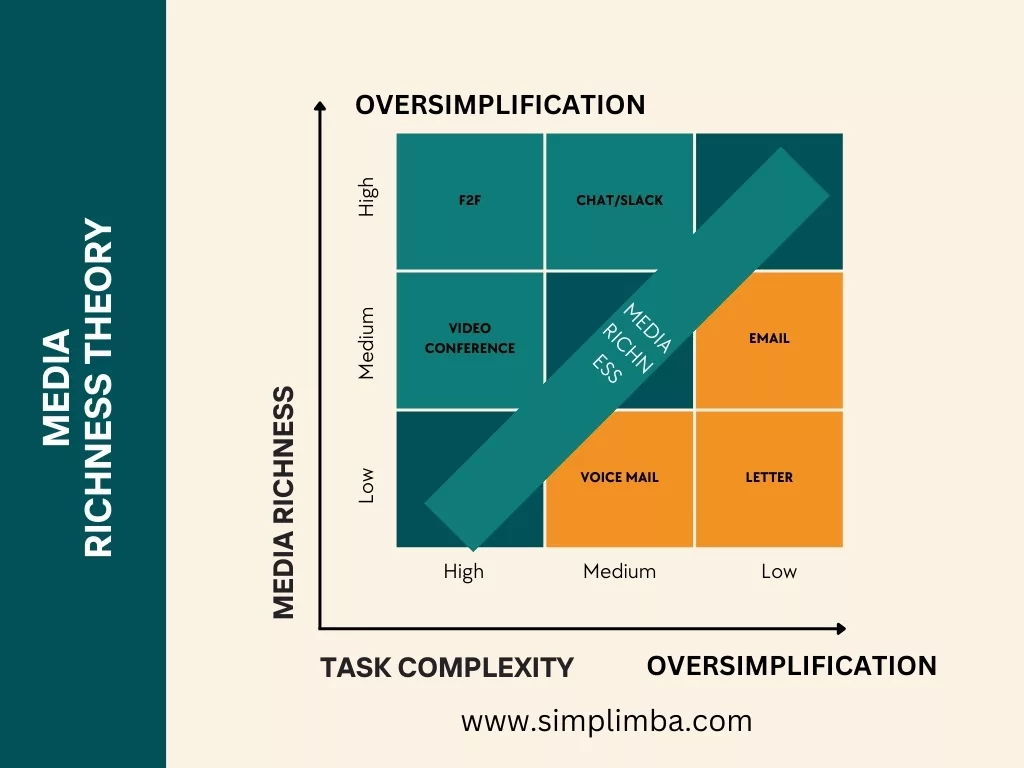

The Media Richness Theory, introduced by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel in 1986, suggests that the effectiveness of a communication medium depends on its ‘richness’ – its ability to convey information accurately and quickly. The ‘richness’ of a medium is determined by four factors: the capacity for immediate feedback; the use of multiple cues like voice, body language, and words; the use of natural language rather than formal, structured language; and the personal focus of the medium.

For instance, face-to-face communication is considered the richest medium as it allows for immediate feedback, utilizes multiple cues, employs natural language, and has a high level of personal focus. On the other hand, a medium like email would be considered less rich as it lacks immediate feedback and the use of multiple cues.

The Media Richness Theory was developed in the context of organizational communication, where Daft and Lengel were trying to understand how managers could select the most effective communication medium to reduce uncertainty and ambiguity in their organizations. Their research identified a spectrum of media richness, with face-to-face communication at one end and written documents at the other.

In today’s digital age, the Media Richness Theory holds significant relevance. With the proliferation of various communication channels – from social media and instant messaging apps to video conferencing tools – understanding the ‘richness’ of each medium is crucial for effective communication.

For instance, a brand launching a new product might choose to do a live video presentation (a rich medium) to fully showcase the product and allow for immediate feedback through comments or reactions. However, for routine updates or announcements, a less rich medium like email or a social media post might suffice.

The Media Richness Theory also helps in tailoring marketing messages. For instance, emotional or complex messages that require a high degree of understanding and empathy might be better communicated through rich media like video or personal storytelling, while simple, straightforward messages can be effectively delivered through less rich media like text messages or posts.

Diffusion of Innovations Theory

The Diffusion of Innovations Theory, first proposed by sociologist Everett Rogers in 1962, is a model that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread through cultures. The theory is built around the premise that adopters of any new innovation or idea can be categorized into five distinct groups based on their readiness to adopt: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

The crux of this theory is that each category of adopters is influenced by different factors and communication channels. For instance, innovators are willing to take risks and are often the first to adopt a new idea or technology. They rely heavily on scientific sources and close contact with other innovators. Early adopters, on the other hand, are more discrete in adoption choices than innovators. They use judicious choice of adoption to help them maintain a central communication position in their social networks.

A classic example of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory in action is the adoption of smartphones. Innovators were the first to adopt this technology when it was still new and expensive. Early adopters came next, influenced by the positive experiences and reviews of the innovators. The early and late majorities followed suit, with the laggards being the last to adopt this technology, often only doing so when it became a necessity.

Since its inception, the Diffusion of Innovations Theory has been widely applied in various fields, including marketing, public health, and mass communication. In the realm of mass communication, this theory is particularly relevant as it provides a framework for understanding how information spreads across different segments of the population. It allows communication strategists to identify key influencers within a network (innovators and early adopters) and target them to speed up the diffusion process.

In the digital age, this theory is even more pertinent. With the rapid proliferation of new media technologies and platforms, understanding the diffusion process can help businesses and organizations to effectively roll out new products, services, or campaigns, ensuring they reach their target audience in the most efficient way possible.

Knowledge Gap Theory

Information is not distributed equally in society, leading to a gap between information-rich and information-poor people. The Knowledge Gap Theory was first proposed by Philip J. Tichenor, George A. Donohue, and Clarice N. Olien from the University of Minnesota in 1970. The theory suggests that there is a significant disparity in the acquisition of knowledge between people who have access to information and those who do not. According to the theory, this gap is primarily due to differences in socioeconomic status, education level, and the amount of media exposure.

In simpler terms, the theory posits that people with higher socio-economic status tend to have better access to information and are more equipped to comprehend and use it. On the other hand, people with lower socio-economic status have less access to information and often lack the necessary skills to understand and use it effectively. This disparity leads to a “knowledge gap” in society.

For example, in the context of health information, an individual with a higher socio-economic status may have better access to health-related information through various sources such as the internet, health magazines, and personal doctors. They are also more likely to have the education and comprehension skills to understand this information and use it to make informed health decisions. Conversely, an individual with lower socio-economic status may not have the same access to this information or the ability to comprehend it, leading to a knowledge gap.

This theory has significant implications in the field of mass communication, especially in the era of digital information. With the advent of the internet and digital media, access to information has increased exponentially. However, the knowledge gap persists due to disparities in digital literacy and access to digital resources. This has led to a new form of knowledge gap known as the “digital divide”.

In the modern context, the Knowledge Gap Theory underscores the importance of ensuring equal access to information and promoting digital literacy. It also highlights the role of mass communication in bridging this gap by making information accessible and understandable to all sections of society. It serves as a reminder for copywriters and marketers to consider the diverse backgrounds of their target audience and craft messages that are not only persuasive but also accessible and comprehensible to everyone.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

Explains how attitudes are formed and changed. The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) is a theory in psychology that describes how attitudes are formed and changed. Developed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in the 1980s, this model suggests that persuasion occurs through two distinct routes: the central route and the peripheral route.

The central route involves careful scrutiny and thoughtful consideration of the message’s content. This route is typically engaged when the audience is highly involved, interested, and motivated. For instance, if a person is considering buying a new car, they might pay close attention to the car’s features, safety ratings, and customer reviews. They are likely to be persuaded by strong arguments and factual evidence.

On the other hand, the peripheral route involves less cognitive effort and is influenced more by superficial cues such as the attractiveness of the speaker, the length of the message, or the credibility of the source. For example, a person might choose a soft drink because they like the celebrity endorsing it, not necessarily because they believe it’s the best product.

In modern-day mass communication, the ELM is highly relevant. Advertisers and marketers often use both routes to persuade their target audience. For instance, a skincare brand might use a celebrity endorsement (peripheral cue) while also providing scientific evidence about the effectiveness of their product (central route). Understanding the ELM can help copywriters craft more persuasive messages by targeting both the thoughtful and superficial influences on their audience’s attitudes.

Moreover, this model underscores the importance of understanding your audience’s level of involvement and interest. For highly involved audiences, copywriters should focus on creating compelling, evidence-based arguments. For less involved audiences, attention should be given to enhancing the attractiveness and credibility of the message and its source.

Social Judgment Theory

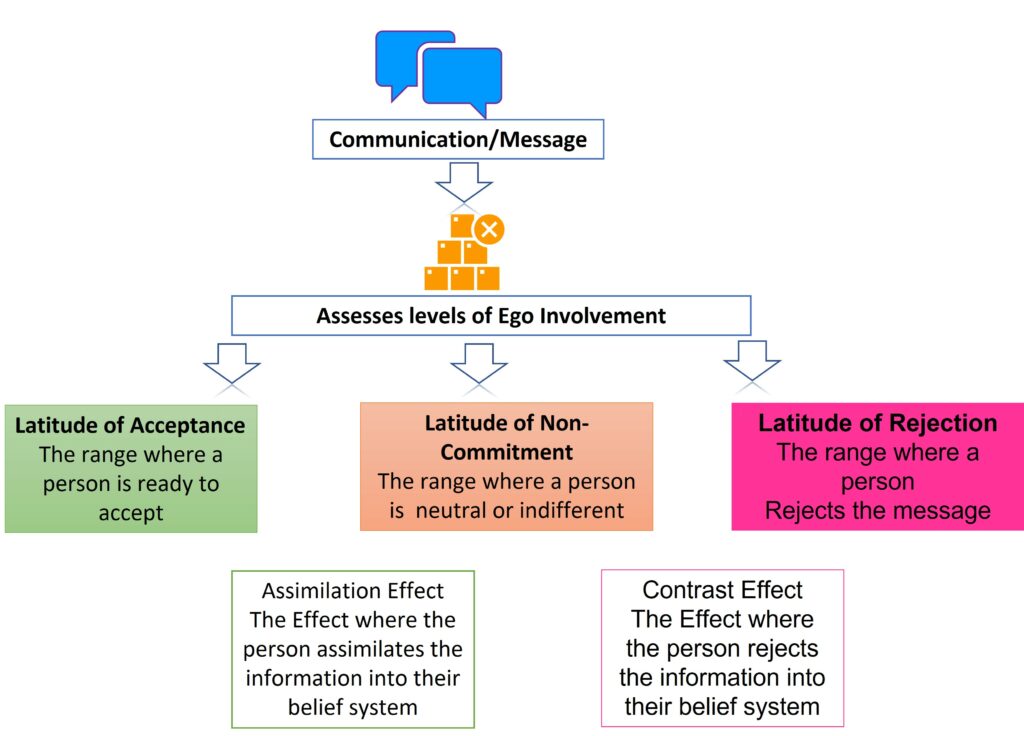

Perception and evaluation of an idea by comparing it with current attitudes. Social Judgment Theory, first proposed by psychologist Muzafer Sherif in 1961, is a communication theory that focuses on how people perceive and evaluate ideas by comparing them with their current attitudes. It is based on the premise that people have a range of opinions on a certain topic, known as the latitude of acceptance, rejection, and non-commitment. These latitudes serve as benchmarks against which new ideas or messages are judged.

For instance, let’s consider a person who is a staunch environmentalist. When exposed to a message advocating for stricter pollution controls, they are likely to judge this message favorably, as it aligns with their latitude of acceptance. On the other hand, a message promoting the benefits of coal mining would fall within their latitude of rejection and would be judged unfavorably. A message that is neutral or ambiguous about environmental issues might fall within their latitude of non-commitment.

The theory was developed in the context of social psychology, but it has since found broad application in the field of mass communication, particularly in the areas of persuasion and attitude change. It helps communicators understand how to craft messages that will be accepted and internalized by their target audience. For example, a public health campaign aiming to change attitudes about smoking might use Social Judgment Theory to craft messages that fall within the audience’s latitude of acceptance or non-commitment, thereby increasing the likelihood of attitude change.

In today’s digital age, the Social Judgment Theory is still highly relevant. With the rise of social media and other digital communication platforms, messages are disseminated more widely and rapidly than ever before. Understanding how audiences judge these messages can help communicators craft more effective, persuasive content. Whether it’s a political campaign, an advertisement, or a public health message, Social Judgment Theory offers valuable insights into how to influence attitudes and behaviors.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory

We strive for consistency in our beliefs. If a belief and a behavior conflict, we are likely to change the belief to fit the behavior. Cognitive Dissonance Theory, proposed by social psychologist Leon Festinger in 1957, is a powerful concept that explains the inner tension or discomfort we feel when our beliefs and behaviors are inconsistent. This theory is based on the premise that as humans, we have an inherent desire for harmony in our thoughts, beliefs, and actions. When there is a discrepancy or dissonance, we strive to reduce it and achieve balance or consonance.

An example of cognitive dissonance could be a person who is conscious about their health and fitness but also enjoys smoking. The conflict between their health-conscious belief and the behavior of smoking creates dissonance. To reduce this dissonance, they may either quit smoking (change behavior) or convince themselves that smoking doesn’t significantly affect their health (change belief)

Festinger’s Cognitive Dissonance Theory has had a profound impact on fields like psychology, marketing, and mass communication. It has been extensively used in advertising and persuasion, where marketers create a sense of dissonance in consumers’ minds about their current product (creating a problem) and then present their product as the solution (resolving the dissonance).

In modern-day mass communication, cognitive dissonance plays a crucial role in shaping public opinion and behavior. News outlets and social media platforms often exploit this theory to sway public opinion. For instance, they may present information that contradicts the audience’s current beliefs, causing discomfort and making them more open to new perspectives.

Overall, understanding cognitive dissonance is essential for effective communication and persuasion. It allows us to craft messages that resonate with the audience, create a need for change, and guide them toward the desired action.

Communication Accommodation Theory

People adjust their communication to fit the group they are addressing. The Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT) is a sociolinguistic theory that explores why and how people modify their communication style to match the people they are interacting with. Developed by Howard Giles, a professor of communication, in the 1970s, this theory was initially called the Speech Accommodation Theory. It was later renamed to encompass all forms of communication, not just speech.

The crux of CAT is the concept of ‘accommodation,’ which refers to the adjustments people make in their speech, vocal patterns, gestures, and overall communication style to ‘accommodate’ or match their interlocutor. These adjustments are not just about fitting in; they are also about creating a sense of identity and belonging, reducing social differences, and fostering positive social bonds.

For example, when a person moves to a new region, they might initially speak with a distinct accent that sets them apart from the local population. Over time, they may start to adopt the local accent and speech patterns to blend in and be accepted by the community. This is a practical example of CAT in action.

CAT has a significant role in modern mass communication. In the era of global marketing campaigns and social media, understanding and applying CAT can help brands communicate more effectively with their diverse target audiences. For instance, a global brand might use different communication styles and messaging for its campaigns in different countries, accommodating the local culture, language, and preferences.

Moreover, CAT is also relevant in the context of social and political discourse. Politicians often use accommodation strategies to appeal to different demographic groups. They adjust their language, tone, and even body language to resonate with the audience they are addressing, whether it’s a group of blue-collar workers, university students, or senior citizens.

Expectancy Violations Theory

The Expectancy Violations Theory (EVT) is a communication principle that suggests we have established norms and expectations for human behavior and when these expectations are violated, we pay more attention to the violator. This theory was first proposed by Judee K. Burgoon in the late 1970s as a means to predict and explain the effects of personal space violations.

The crux of EVT is that it’s not necessarily the violation of expectations that causes discomfort or draws attention, but rather how the violation is perceived. For instance, if a person who is generally reserved and introverted suddenly becomes boisterous and outgoing, this unexpected behavior would be a violation of our expectations for that person. However, whether or not this violation is viewed positively or negatively would depend on various factors such as our relationship with the person, the context, and the perceived intention behind the violation.

For example, imagine a scenario where a typically stoic professor unexpectedly cracks a joke in the middle of a serious lecture. This behavior violates students’ expectations, thus drawing their attention. If the joke is well-received, the violation could enhance the professor’s rapport with the students. However, if the joke is inappropriate or poorly timed, it could negatively impact the professor’s credibility.

In terms of its relevance in modern-day mass communication, EVT is particularly significant. With the rise of digital media and social platforms, the line between personal and public space has blurred, and the potential for expectancy violations has increased. When a celebrity or public figure behaves in a way that deviates from their established persona, it often triggers a flurry of media attention and public discussion. For instance, a celebrity known for their wholesome image posting a controversial tweet would be an expectancy violation, and would likely result in increased public scrutiny.

Moreover, EVT is also used as a tool in advertising and marketing. Advertisers may deliberately violate expectations to grab the audience’s attention. For instance, a company known for serious, straightforward ads might suddenly launch a humorous, quirky campaign. This violation of audience expectations can make the advertisement more memorable and impactful.

Narcotizing Dysfunction

The Narcotizing Dysfunction is a theory that emerged from mass communication research. It was first coined by sociologists Paul Lazarsfeld and Robert Merton in the mid-20th century. The theory suggests that as mass media floods people with a high volume of information on a particular issue, these individuals tend to become indifferent or apathetic to it. They mistake their knowledge or awareness of the topic for actual action or involvement.

For instance, consider the issue of climate change. It’s a topic that has been extensively covered by the media, with countless articles, documentaries, and news reports dedicated to it. Due to this constant exposure, many people feel that they are well-informed about the issue. However, this awareness does not necessarily translate into action. People tend to believe that being informed is equivalent to participating or contributing to the cause, which is not the case. This is the crux of the Narcotizing Dysfunction.

This theory is more relevant today than ever before, given the omnipresence of digital media. The internet, social media, and 24/7 news cycles bombard us with information, often leading to information overload. This can result in apathy and a false sense of action, as outlined by the Narcotizing Dysfunction theory.

To counter this dysfunction, it is essential to promote active engagement with issues rather than passive consumption of information. As a society, we must strive to move beyond mere awareness and towards informed action.

In the realm of persuasive writing and marketing, understanding this theory can be crucial. It highlights the need for messages that not only inform but also inspire action. This can be achieved by crafting compelling narratives, making the audience feel a part of the solution, and clearly outlining the steps for them to take action.

Media Ecology Theory

The Media Ecology Theory, originally proposed by Marshall McLuhan, posits that the medium through which information is communicated significantly influences the message itself. It’s not just the content that matters, but the medium through which it is delivered also plays a crucial role in shaping the perception of the message.

McLuhan famously stated, “The medium is the message,” suggesting that the medium used to send a message can impact how the message is received and interpreted. For example, a message delivered through a television commercial may be perceived differently than the same message delivered through a radio advertisement or a newspaper article. The medium used can affect the tone, context, and overall reception of the message.

The Media Ecology Theory also asserts that media environments, the sum of all communication outlets, play a pivotal role in shaping human perception, understanding, feeling, and value. The medium, therefore, becomes an extension of ourselves, influencing how we perceive and interact with the world.

The Media Ecology Theory emerged during the mid-20th century, a time of rapid technological advancements and societal changes. Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian professor, and philosopher, is widely regarded as the father of media ecology. His work focused on understanding the effects of media, technology, and communication modes on human perception and behavior.

In the era of digital communication, the Media Ecology Theory is more relevant than ever. The proliferation of new media platforms like social media, blogs, podcasts, and streaming services has dramatically changed the way messages are delivered and received.

For instance, social media platforms have transformed the way businesses communicate with their customers. Brands can now deliver personalized messages to their target audience, fostering a more intimate and engaging relationship. However, the same platforms have also been used to spread misinformation, demonstrating the significant influence of the medium on the message.

Third-Person Effect

People believe others are more affected by media messages than they are themselves. The Third-Person Effect is a fascinating psychological theory that was first proposed by sociologist W. Phillips Davison in 1983. The core concept of this theory is that individuals tend to believe that mass communications (such as advertisements, news reports, or public service announcements) have a greater influence on others than on themselves. This perception gap, where one underestimates the impact of media messages on one’s own behavior while overestimating its effect on others, is the crux of the Third-Person Effect.

For instance, consider a television commercial for a fast food chain. While many viewers might believe that such advertising would influence others to eat more fast food, they might simultaneously believe that they themselves are immune to such persuasion. In reality, however, they may be just as influenced as they perceive others to be.

Since its inception, the Third-Person Effect has been widely studied and applied in various fields, particularly in mass communication and marketing. It has been used to explain various societal behaviors and attitudes, such as public support for media censorship, the spread of fake news, and the perception of political campaign effects.

In the modern age of digital communication, the Third-Person Effect theory remains highly relevant. With the proliferation of social media and the increasing personalization of advertising, individuals are exposed to more persuasive messages than ever before. Understanding this theory can help marketers and advertisers craft more effective communication strategies. It can also help individuals become more aware of their susceptibility to media influence, encouraging a more critical consumption of media content.

Political Economy Theory

The struggle over power and wealth influences the content and distribution of media.The Political Economy Theory, at its core, is a social theory that deals with the interplay between political and economic forces in society. It posits that the power and wealth dynamics within a society significantly influence the content and distribution of media.

The crux of this theory is that media is not just a tool for information dissemination, but a platform where power and economic interests are negotiated and expressed. For instance, large media conglomerates may use their platforms to promote political ideologies or economic interests that align with their own, thereby shaping public opinion in their favor. This could be seen in the way certain news outlets cover political events or economic policies, highlighting aspects that favor their interests while downplaying or ignoring those that don’t.

The Political Economy Theory has its roots in the works of classical economists like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Stuart Mill who explored the relationship between political power and economic wealth. However, it gained prominence in media studies in the late 20th century, with scholars like Dallas Smythe and Robert McChesney expanding its application to understand the influence of media ownership and commercial pressures on media content.

In the modern context of mass communication, the Political Economy Theory is more relevant than ever. With the rise of digital media and the increasing concentration of media ownership, the power to control the narrative has become centralized in the hands of a few. This can lead to a skewed representation of reality, where the interests of the powerful are prioritized over the needs and concerns of the average citizen.

As a result, understanding the Political Economy Theory can help us critically analyze the media content we consume and recognize the underlying power dynamics at play. It reminds us that media is not a neutral platform, but a battleground where different interests vie for dominance. As such, it is incumbent upon us as consumers to question, critique, and demand media that is fair, balanced, and representative of diverse voices in society.

Each of these theories offers unique insights into the complex processes of mass communication. They help us to understand how media influences our perceptions, behaviors, and attitudes, and how we, in turn, use media to interact with the world around us.

| Theory | Points of Difference | History | Crux | Relevance |

| WHAT IS? | WHEN? | CARE FOR A SUMMARY? | IMPORTANCE TODAY? | |

| Agenda-Setting Theory | Focuses on how media influences what topics are considered important. | Developed by Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw in the 1960s. | People use media for their purposes, such as information, personal identity, integration, and entertainment. | Crucial in shaping public opinion and political discourse. |

| Cultivation Theory | Argues that media shapes our perception of reality over time. | Developed by George Gerbner in the 1970s. | Heavy media consumption leads to a perception of reality that aligns with the media’s portrayal. | Helps understand the impact of long-term media exposure on audiences. |

| Spiral of Silence Theory | Suggests people remain silent when they feel their views are in the minority. | Introduced by Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann in 1974. | Fear of isolation leads to silence, which perpetuates the perceived dominance of the majority view. | Offers insights into why people may not voice their opinions. |

| Uses and Gratifications Theory | Proposes that people actively seek out media to fulfill certain needs or desires. | Developed by Elihu Katz in the 1970s. | People use media for their own purposes, such as information, personal identity, integration, and entertainment. | Helps understand why people choose certain media over others. |

| Media Dependency Theory | Suggests that the more dependent an individual is on the media for having their needs fulfilled, the more important the media will be to that person. | Developed by Sandra Ball-Rokeach and Melvin DeFleur in 1976. | The media’s influence varies depending on how much a person relies on it. | Highlights the influence of media on people’s lives. |

| Social Learning Theory | Posits that people learn from observing others’ behavior, attitudes, and outcomes of those behaviors. | Developed by Albert Bandura in the 1960s. | Media can influence behavior through observational learning. | Explains how media can shape behavior and attitudes. |

| Gatekeeping Theory | Holds that media has the power to decide which stories are told and how. | Introduced by Kurt Lewin in 1947. | Journalists and editors act as “gatekeepers,” controlling the flow of information. | Highlights the role of media in shaping news narratives. |

| Two-Step Flow Theory | Suggests that media influence often works in two stages—media content is picked up by “opinion leaders” who then pass on their interpretations to others. | Developed by Paul Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, and Hazel Gaudet in 1944. | Media’s influence is indirect and filtered through opinion leaders. | Explains how public opinion is formed. |

| Hypodermic Needle Theory | Early theory on media’s influence, is largely discredited today. | Originated in the 1930s. | Media can inject ideas and messages directly into the passive audience. | The media doesn’t tell us what to think, but what to think about. |

| Selective Exposure Theory | Argues that media messages have a direct, powerful, and uniform effect on individuals. | Developed by Leon Festinger in the 1950s. | People seek out media that aligns with their beliefs and avoid conflicting information. | Explains the rise of echo chambers and polarization. |

| Framing Theory | Suggests that how an issue is framed can significantly affect decisions and judgments. | Developed by Erving Goffman in the 1970s. | Media frames shape how we understand and interpret the world. | Highlights the power of media in shaping perceptions. |

| Priming Theory | Asserts that media can subtly shape our perceptions and interpretations by priming certain ideas or themes. | Developed in the 1980s. | Media primes certain associations, influencing subsequent thoughts and judgments. | Explains how media can subtly influence attitudes and beliefs. |

| Symbolic Interactionism | Focuses on the symbolic meaning that people develop and rely upon in the process of social interaction. | Developed by George Herbert Mead in the early 20th century. | Communication is symbolic and shapes our understanding of the world. | Helps understand how people interpret media messages. |

| Media Richness Theory | Proposes that communication channels have different capacities to convey information effectively. | Introduced by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel in 1986. | Different media have different “richness” levels, affecting how well they convey information. | Useful in choosing the right medium for communication. |

| Diffusion of Innovations Theory | Explains how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread. | Developed by Everett Rogers in 1962. | Innovations spread through social networks in a predictable pattern. | Helps understand the adoption of new ideas and technologies. |

| Knowledge Gap Theory | Suggests that information dissemination often benefits those who already have a knowledge base. | Introduced by Philip J. Tichenor, George A. Donohue, and Clarice N. Olien in 1970. | Information tends to widen the knowledge gap between different social groups. | Highlights inequality in access to information. |

| Elaboration Likelihood Model | Proposes two routes to persuasion: a central route and a peripheral route. | Developed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in the 1980s. | Persuasion depends on the degree of cognitive processing (elaboration). | Useful in designing persuasive messages. |

| Social Judgment Theory | Suggests that people have different ranges of acceptance, rejection, and non-commitment towards ideas. | Developed by Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland in 1961. | People categorize new information based on their current attitudes. | Helps understand how people form judgments. |

| Cognitive Dissonance Theory | Argues that people strive for internal consistency, and experience discomfort (dissonance) when they hold conflicting cognitions. | Introduced by Leon Festinger in 1957. | People seek consistency in their beliefs and attitudes, and will adjust them to reduce dissonance. | Explains why people change their minds or rationalize their decisions. |

| Communication Accommodation Theory | Explains how people adjust their communication to facilitate understanding. | Developed by Howard Giles in 1973. | People adapt their communication style to accommodate others. | Helps understand intergroup communication and social identity. |

| Expectancy Violations Theory | Suggests that people have expectations about nonverbal behavior and react when those expectations are violated. | Developed by Judee K. Burgoon in the 1970s. | Violations of nonverbal expectations can be positive or negative, depending on the violator’s reward value. | Helps understand the impact of nonverbal behavior in communication. |

| Narcotizing Dysfunction | Proposes that mass media can overwhelm people to the point where they become apathetic. | Introduced by Paul F. Lazarsfeld and Robert K. Merton in 1948. | Overexposure to media can lead to apathy and inaction. | Highlights the potential negative effects of excessive media consumption. |

| Media Ecology Theory | Studies how media and communication processes affect human perception and understanding. | Developed by Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s. | “The medium is the message” – the medium influences how the message is perceived. | Helps understand the impact of media on culture and society. |

| Third-Person Effect | Suggests that people believe others are more affected by media messages than they are themselves. | Introduced by W. Phillips Davison in 1983. | People underestimate media’s effect on themselves and overestimate its effect on others. | Highlights the perceptual bias in media effects. |

| Political Economy Theory | Examines the interplay between the media industry and the political and economic forces. | Developed as a critique of mass media in the 20th century. | Media is shaped by and contributes to the political and economic structures. | Helps understand the role of media in power structures. |

Samrat is a Delhi-based MBA from the Indian Institute of Management. He is a Strategy, AI, and Marketing Enthusiast and passionately writes about core and emerging topics in Management studies. Reach out to his LinkedIn for a discussion or follow his Quora Page